3 - Rational Attackers

In §2 we discussed how costless simulation opens attack vectors for double spending in longest-chain blockchains and how these are addressed in . To show security we assumed that a sufficient fraction of the resource is controlled by honest parties who follow the protocol rules. In reality it's unrealistic to assume that parties will behave altruistically, instead we need to argue that it's rational for parties to follow the protocol rules. Unfortunately costless simulation also makes this task much more challenging than in a PoW based system.

In analogy to selfish mining in Bitcoin, we refer to strategies by which a party gets more rewards than they would by following the protocol rules as selfish farming. To argue that rational parties will behave honestly it's necessary to bound the efficacy of selfish mining/farming strategies. To argue that rational parties will behave honestly it's necessary to bound the efficacy of selfish mining/farming strategies.

In §3.1 below we first discuss selfish mining and why we don't observe it in Bitcoin even though it's possible in principle. As directly analyzing the security of a longest-chain protocol against selfish mining/farming is very challenging we take a modular approach. In §3.1 below we first discuss selfish mining and why we don't observe it in Bitcoin even though it's possible in principle. As directly analyzing the security of a longest-chain protocol against selfish mining/farming is very challenging we take a modular approach. In §3.2 we first identify two properties – no slowdown and delayed gratification illustrated in Figure 5 – which are satisfied by Bitcoin, and then show in §3.3 that they imply robustness against selfish mining (through the notion of chain quality) of the level as achieved by Bitcoin. In §3.4 and §3.5 we then sketch how those notions are achieved in . In §3.4 and §3.5 we then sketch how those notions are achieved in .

3.1 Selfish Mining in Bitcoin

While Bitcoin prevents double spending assuming a majority of the hashing power is controlled by miners who altruistically follow the protocol, it allows for selfish mining [ES18] by which a miner with a fraction of the hashing power can create more than an fraction of the blocks and thus gets an unfair share of the block rewards. In some settings this fraction can be as large as (e.g. a fraction for ).1 Selfish mining has not been observed in Bitcoin, and there are various reasons why this is the case

-

selfish mining requires either a fairly large fraction of the hashing power or very good control of the network (cf. Footnote 1) to be profitable

-

the attack would be easily detected and

-

delayed gratification as defined below.

3.2 Delayed Gratification and No Slowdown

The Bitcoin blockchain is split in epochs, each with a targeted duration of two weeks, and only at the end of an epoch the difficulty is reset to accommodate for the variation of the hashing power. Assuming the network is reliable, within an epoch, a selfish miner cannot create more blocks than they would get by honest mining. This follows from a crucial property of proofs of work: there's no way to find more proofs of a given difficulty (and thus blocks) in a given time window than simply following the protocol and always working on the known longest chain. The only thing selfish mining does in Bitcoin is to make honest parties waste their hashing power, so after the next difficulty reset (which only happens every 2 weeks) the difficulty is lower than it should be, and only at this point the selfish miner makes some extra profit. Another property of PoW based chains like Bitcoin is that an adversary cannot slow down chain growth. We capture these two desirable properties separately below.

Delayed Gratification: A chain where an adversary cannot increase the number of blocks they find in expectation within an epoch of same difficulty by deviating from the honest strategy is said to have the delayed gratification property. In , by "not deviating" we mean that the adversary simply runs an honest farmer using its available space, and additionally, should the adversary control VDFs that are faster than the fastest honest time lord, they are also assumed to run a time lord. Intuitively, delayed gratification is a good deterrent to selfish mining by itself as it limits selfish mining to adversaries who follow a "long term" agenda. In , by "not deviating" we mean that the adversary simply runs an honest farmer using its available space, and additionally, should the adversary control VDFs that are faster than the fastest honest time lord, they are also assumed to run a time lord. Intuitively, delayed gratification is a good deterrent to selfish mining by itself as it limits selfish mining to adversaries who follow a "long term" agenda.

No Slowdown: A chain where an adversary (no matter what fraction of the resource they control) cannot slow down the expected block arrival time by interacting with the chain is said to have the no slowdown property.

3.3 Chain Quality

A longest-chain blockchain is said to have chain quality if the fraction of blocks mined by honest miners is at least (with high probability and considering a sufficiently large number of blocks). Chain quality was introduced in [GKL15] as a metric to quantify how susceptible a chain is to selfish mining. Ideally, assuming an adversarial miner who controls an fraction of the resource, the chain quality should be as this means that the adversary cannot increase its fraction of blocks by deviating. Chain quality was introduced in [GKL15] as a metric to quantify how susceptible a chain is to selfish mining. Ideally, assuming an adversarial miner who controls an fraction of the resource, the chain quality should be as this means that the adversary cannot increase its fraction of blocks by deviating.

By the Proposition below delayed gratification and the no slowdown property imply a bound on chain quality which matches the bound proven for Bitcoin (when ignoring network delays).

Proposition 1 (Delayed Gratification and No Slowdown implies Chain Quality). Proposition 1 (Delayed Gratification and No Slowdown implies Chain Quality). Consider a longest-chain protocol which has the delayed gratification and no slowdown property against an adversary who controls an fraction of the global resource, then the chain quality is (compared to the ideal ).

Proof. Consider an adversarial miner with an fraction of the resource and let denote the (expected) number of blocks to be found if everyone would mine honestly. By the no slowdown property, no matter what does the number of blocks found is at least . By delayed gratification, at most of those blocks were created by , we get a chain quality of By the no slowdown property, no matter what does the number of blocks found is at least . By delayed gratification, at most of those blocks were created by , we get a chain quality of

3.4 Delayed Gratification in Chia

Having motivated why the no slowdown and delayed gratification properties are useful, in this and the next section we will sketch how they are achieved in Chia. Recall that delayed gratification means a selfish farmer cannot add more blocks into the chain than he could by honestly following the protocol. To achieve this in we ensure that

(a) a challenge is revealed as late as possible.

(b)) once it's revealed, it's almost certainly too late for a selfish farmer to influence it in any way.

(c)) whether a plot can produce a block for a challenge only depends on the plot and the challenge (and not say, on what other plots exist).

These properties imply delayed gratification as a selfish farmer cannot do anything to influence challenges in a controlled way due to (a) & (b), and cannot do anything to increase its number of winning blocks for a given challenge due to (c).

We will sketch how properties (a)-(c) are achieved in next. To follow the arguments the reader might want to recap the high level outline in §1.7 and illustration in Figure 1

(a) The only reason for the infused challenge chain is to make sure that the challenge becomes known as late as possible, in particular when considering an adversary with a faster VDF than the fastest honest time lord.

(b) We infuse the first block of each slot into the challenge chain , this way making sure that this block is buried deep in the chain (by blocks on average) once revealed, and thus almost impossible to revert.

(c) We use a variation on the correlated randomness technique from [BDK+19], where we let the challenge depend on every th challenge on average, rather than exactly. This way only the challenge determines whether a plot can produce a winning block, irrespective of what other plots exist.

3.5 No-Slowdown of Chia and other Constructions {#s:nschia}

Recall that the no slowdown property requires that no adversary can slow down the block arrival time by participating.

3.5.1 No-Slowdown in Bitcoin

In Bitcoin no slowdown holds as whenever an honest miner finds a block, all the honest miners will switch to a heavier chain. An adversary can still kick out this block and replace it with one of his own (and that's what selfish mining is exploiting), but not slow down the growth. Of course here we assume a reliable network, a network level attacker who can increase the latency or even split the network can of course delay chain growth.

3.5.2 A Non-Example, the G-Greedy-Rule

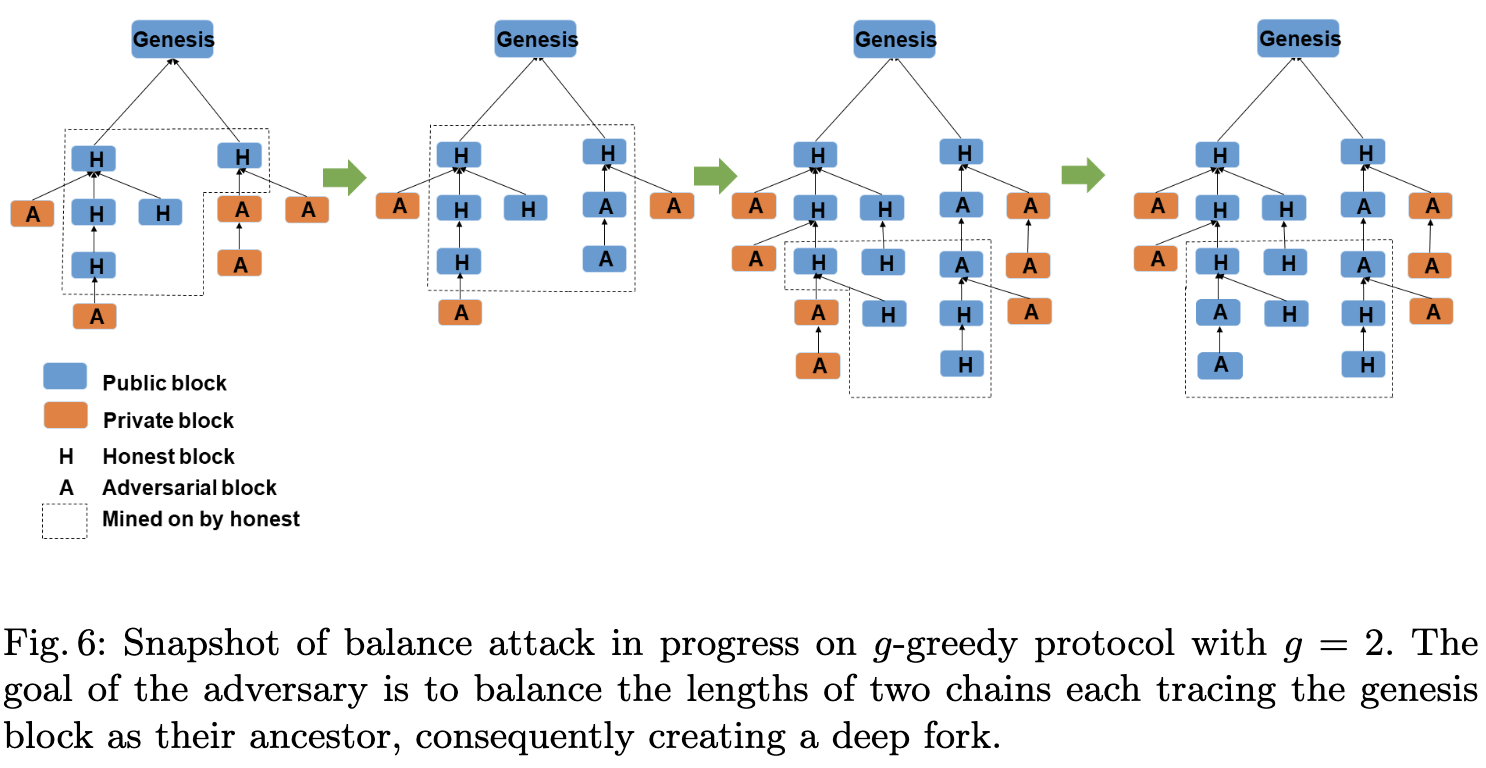

One might assume that the no-slowdown property would be achieved by any "natural" longest-chain blockchain even if based on efficient proof systems. Unfortunately this intuition is wrong. A design for which no-slowdown fails to hold is the proof of stake based chain of Fan and Zhou [FZ17]. Their chain mimics Bitcoin's Nakamoto consensus using proofs of stake, but to harden the design against (what in this writeup is called) double dipping attacks [FZ17] suggest the miners not only extend the longest chain, but instead follow the "-greedy rule": a miner should try to extend all forks they see which are at most blocks shorter than the longest chain they've seen so far. The rationale behind this rule is that by letting the honest miners do double-dipping to some extent, the advantage an adversary can get by double dipping shrinks.2 As shown in [BDK+19], this design has some serious issues as an adversary with relatively small resources can with high probability prevent the chain reaching consensus by strategically releasing blocks and this way keep two forks alive for a long time. An illustration of their attack is in Figure 5. Interestingly (citing [BDK+19]) "..the efficacy (of the attack) is primarily achieved by slowing down the growth rate of the honest strategy."

3.5.3 Examples of No-Slowdown.

The lesson from the example above is that the no-slowdown property is not easy to achieve in longest-chain protocols using efficient proof systems. Moreover the absence of this property can lead to various security issues, not just selfish mining opportunities, but even prevent consensus almost indefinitely as in the example above. Similar attacks were also proposed for BFT type protocol, most notably Ethereum [SNM+21].

Naïve Emulation of Bitcoin

There are longest-chain blockchains from efficient proof systems which do have the no-slowdown property. The simplest is to just emulate Bitcoin by replacing PoW with PoSpace or PoStake. While satisfying no-slowdown, this basic construction has all the security issues discussed in §2. Fixing bootstrapping and grinding as outlined in §2 will preserve the no-slowdown property. The challenge is to find a good countermeasure to double-dipping without losing the no-slowdown property and introducing new attack vectors.

-Distance Greedy

Bagaria et al. [BDK+19] not only prove that -greedy does not have the no-slowdown property, but also suggest a different rule of a similar flavour they call "-distance greedy", for which the no-slowdown property does hold [BDK+19 Lemma 12]. This rule reduces the double-dipping advantage factor towards as increases, but already for moderately large it becomes computationally infeasible for the miners to even determine which chain to follow.

Old

The first Chia greenpaper [CP19] has a very simple rule where honest farmers try to extend the first ( was suggested) chain of any given length they become aware of. For this simple construction the advantage factor of double-dipping goes to as increases while it does achieve no-slowdown [CP19 Lemma 4].

While the deployed blockchain has many advantages over the old [CP19] proposal, the no-slowdown property is a much tricker issue in the new design. In particular, we do not yet have an analogue of [CP19 Lemma 4] which basically states that even an unbounded adversary (unlimited space, unlimited number of arbitrary fast VDFs) cannot slow down chain growth.

When analyzing the no-slowdown property, it is useful to distinguish the specification of the chain (i.e., what constitutes a valid chain) and its chain selection rule (aka. fork choice rule), which tells the farmers and time lords on which chains to work should competing forks exist.

For example the difference in the -greedy and the -distance greedy protocols discussed above (only the latter having the no-slowdown property) is only in the chain selection rule, the specification what constitutes an valid chain is the same.

Unlike the chain specification, which can only be changed by a hard fork once the chain is deployed, the chain selection rule can easily be adapted by the farmers and/or time lords even after the launch. Finding a chain-selection rule for the chain which provably achieves no-slowdown is an interesting open problem.

Under the additional assumption that an adversary does not control VDFs which are faster than the fastest honest time lord, a very simple chain selection rule achieving no-slowdown exists: always follow the chain with accumulated most VDF steps. Of course this rule would be terrible in practice as security completely breaks if the adversary has an even slightly faster VDF than the fastest honest time lord. For example, such an adversary could create an "empty" chain by refusing to infuse any blocks. Of course this rule would be terrible in practice as security completely breaks if the adversary has an even slightly faster VDF than the fastest honest time lord. For example, such an adversary could create an "empty" chain by refusing to infuse any blocks.

A more sensible rule is to simply follow the heaviest fork like in Bitcoin. Unfortunately, unlike in Bitcoin, in the heaviest fork is not necessarily the fork which will be heaviest in the future assuming all honest parties adapt it: a fork might have one more block infused than some fork , but if is way ahead in the VDF computation extending might give a better chain (in expectation) in the future. Thus, when using this rule, by releasing an adversary might slow down the chain. The currently deployed chain selection rule for farmers and time lords is basically to follow the heaviest fork, but with some heuristics to avoid clear cases where switching to a heavier chain is slowing down growth.

Footnotes

-

To achieve such a large fraction we must assume that (1) honest miners follow the (original Bitcoin) rule and in case they learn of two longest chains they always try to extend the one they saw first and (2) that once the selfish miner learns about a block mined by the honest miners, they can release a withheld block such that their block reaches most of the honest miners faster than this honest block. If either of these conditions is not met, selfish mining is much less profitable, and only becomes profitable at all for selfish miners who control a fairly large fraction of the resource [SSZ15]. ↩ ↩2

-

A similar proposal, where the honest parties try to extend the first blocks they see at every depth was proposed in an early proposal for (with ) [CP19]. This variant achieves the no-slowdown property. ↩