6 - Recovering from 51% Attacks and Dynamic Availability

In this Section we have a look at two closely related security properties of longest-chain blockchains, namely recovery from malicious majority (aka. 51% attacks) and security under dynamic availability. We'll discuss proofs of work, stake and space, for the latter two also looking at how adding VDFs changes the picture.

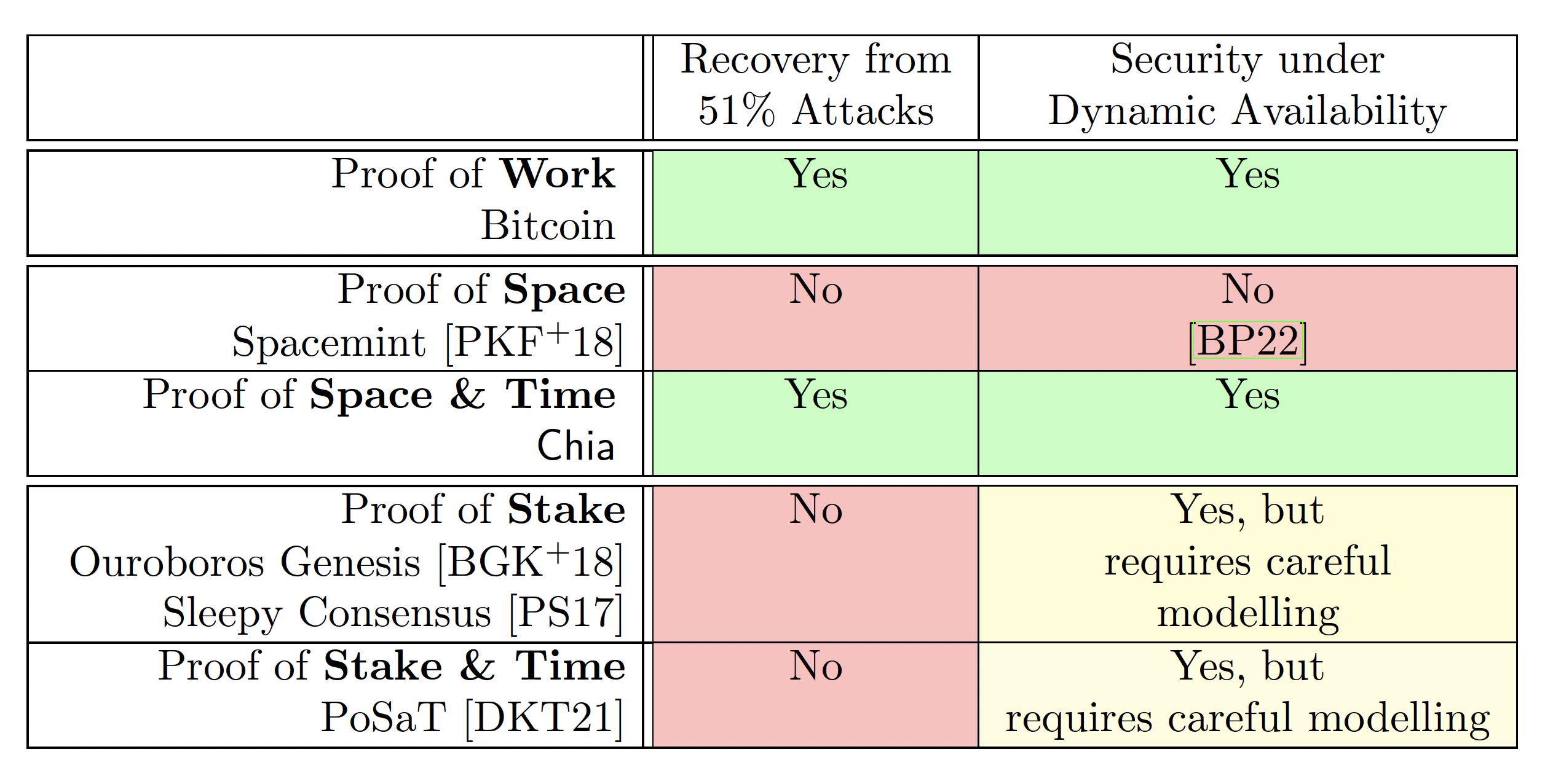

We discussed in §2 the main security issues of a PoSpace based longest-chain blockchain arise from the fact that PoSpace is an efficient proof system. PoSpace shares those security challenges with PoStake, and all three countermeasures summarized in Figure 3 (namely splitting the chain to prevent grinding, correlated randomness to prevent double-dipping and using VDFs to prevent bootstrapping) can readily be applied in the stake setting, correlated randomness was even originally proposed for stake [BDK+19]. But as we'll discuss below, when it comes to security under dynamic availability or 51% attacks there are fundamental differences between space and stake. In particular, using proofs of space in combination with VDFs one can handle both attacks basically as well as with proofs of work, while proofs of stake cannot, even in combination with VDFs.

Table 1: Summary of the ability to heal from malicious majority and provide security under dynamic availability of longest-chain protocols based various proof systems.

6.1 Recovery from Attacks

A key difference between a PoW based longest-chain protocol and a longest- chain protocol based on an efficient proof system like PoStake or PoSpace is the fact that only the PoW based chains is guaranteed to recover security once an adversary that controls a sufficiently large fraction of the resource, even if it's just for a short period. This is sometimes called "a attack" referring to the fact that in bitcoin an adversary controlling of the hashing power can break security in pretty much any way they like (they can double spend, get of the block rewards or censor). We'll stick with this expression even though the fraction of the resource required to control a chain can be lower than (as mentioned in §1.1, in controlling of the space is sufficient).

There's also a key difference between PoStake and PoSpace. By using VDFs in addition to PoSpace as in we get a chain that does have this self- healing property. While we can also augment a PoStake based chain with VDFs [DKT21], the resulting chain will not be self-healing.

6.1.1 Recovering from PoW Majority in Bitcoin {#S:RBB}

While Bitcoin provides no security if more than half of the hashrate is controlled by an adversary, it is "self-healing" in the sense that once the majority of the hashrate is again controlled by honest parties, Bitcoin regains (after some delay) all its security properties.

A bit more formally, let and denote the hashing power of the honest and adversarial parties at clock time , respectively. For let

denote the cumulated hashing power in the time window from to . If is the difficulty in this time window,1 then the expected number of blocks found by the honest parties in this time window is .

It's instructive to understand when a transaction is trivially insecure: consider a transaction that is contained in a block attached at time , if one waits for blocks on top before considering the transaction confirmed (for Bitcoin is often suggested), then an adversary can fork the chain in order to double spend this transaction with good probability if for some with we have

If this holds the adversary can simply start at time to mine a chain in private, and release it at time . By the first inequality the adversaries chain will be heavier than the honest one with probability at least , and by the 2nd the honest block added at time will be buried by blocks with probability , so both hold and we have a successful double spending attack with probability at least (it can actually be a bit less than that as the two events are negatively correlated).

To be secure it's not sufficient that no as in eq.(11) exist, but one needs to be "sufficiently far" from this situation to guarantee that double spending can only happen with some tiny probability. From the standard Chernoff bound it follows that the probability that a fork starting at a block added at time and being released at time will be successful (i.e., have higher weight than the honest chain) is exponentially small in the number of expected honest blocks and the square of the honest to adversarial advantage, i.e.,

6.1.2 Recovering from PoStake Majority

This is in stark contrast to PoStake based longest-chain protocols, where once an adversary gets hold of keys controlling a sufficiently large amount of stake, security cannot be recovered by the honest parties without resorting on some external mechanism. The reason is bootstrapping as discussed in §2.3: an adversary who holds keys which at some point in the chain controlled stake , can fork at that point and bootstrap a chain to the present that looks as if they had stake throughout. The issue is aggravated due to "stake-bleeding" [GKR18], which refers to the fact that the fork can amass additional stake through fees and block-rewards.

6.1.3 Recovering from PoSpace Majority

A longest-chain protocol using only PoSpace (like Spacemint [PKF+18]) is basically as bad as PoStake based protocols when it comes to healing after an adversary got control of a large amount of the resource. One difference is that in the PoStake case the bootstrapping is only possible while the adversary holds the space resource, while bootstrapping in PoStake just requires keys that were valid at some point in the past but can be worthless (i.e., not hold any stake in the chain currently considered by the honest parties) now. On the positive side, stake-bleeding is not an issues for PoSpace.

6.1.4 Recovering from Space-Time Majority in {#S:RPOST}

While a pure PoSpace based longest-chain protocol fails to heal from adversarial majority due to bootstrapping, by combining space with time as in Chia we prevent bootstrapping, and get a chain that naturally heals from adversarial majority. Though, what exactly constitutes the resource in a PoST protocol is less obvious than e.g. in the PoW or PoSpace setting. We already shortly touched this issue in §1.1. We'll now recap the notion for PoST resources introduced there, but in a more fine-grained manner using a time parameter to reflect that resources can change over time. Let

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| denote the disk space (more precisely, the space with initialised plots) available to the honest and adversarial parties at time , respectively | |

| denote the speed of the (three) VDFs available to the fastest honest and online time lord at time | |

| denote the speed of the VDFs available to the adversary, the number of VDFs available to the adversary is unbounded. |

only considers the fastest honest time lord, as only they matter for the growth of the honest chain. The adversary on the other hand is allowed an unlimited number of VDFs of speed . Not putting any bound here makes the security statements stronger, but it might seem to give the adversary an unrealistic advantage. This is not really the case as most of the advantage an adversary can get by using many VDFs (trough double dipping) can already be achieved by using a fairly low amount of VDFs. So it would hardly make a quantitative difference if we put a cap on the number of VDFs, say 100, or simply put no cap at all.

Define the honest and adversarial resource at time time as the product of their space and VDF speed

and analogously to the work setting let the cumulative space-time resource in a window from to be

With these definitions we now get a similar bound on the probability that an adversary can create a fork starting at and being released at time as we did for PoW in eq.(12)

A difference to the PoW setting is the additional factor boosting the adversary's resource which is necessary to account for the fact that they can do some bounded double dipping.

Analogously to the PoW case, a block added at time can be considered secure even in a setting where the adversary can get temporary majority as long as for all where is large enough for the block added at time to be considered confirmed at time , the probability in eq.(13) is small.

6.2 Dynamic Availability

A blockchain based on some resource is secure under dynamic availability if it's security properties hold even if the amount of the resource dedicated towards securing the chain varies over time as long as at any point in time the honest parties control sufficiently more of the resource than a potential adversary.

6.2.1 Dynamic Availability for PoW (Bitcoin)

Using notation from §6.1.1, for a PoW based chain that means that for some (that captures the advantage of the honest parties) and any time we have

To see that Bitcoin is secure under dynamic availability we can reuse our inequality eq.(12) which using simplifies to (recall that is the expected number of honest blocks in the to window)

Which simply means that the probability that an adversary will be able to create any particular a fork decreases exponentially in the length of the fork.

6.2.2 Dynamic Availability for PoST ()

Analogously to PoW just outlined, and using notation from §6.1.4 we can define dynamic availability for PoST as used in by requiring that at any time

With this eq.(13) becomes

Thus like in Bitcoin, in the probability of a successful fork decreases exponentially fast in the length of the fork.

Unlike for PoW, to guarantee security it's not sufficient that , but we need a more substantial gap in the resources of the honest parties and the adversary to account for double dipping, for parameters as in is sufficient.

6.2.3 Dynamic Availability from PoSpace {#S:DAspace}

While in we achieve security under dynamic availability by using space and time as a resource, it's an intriguing question whether a longest-chain blockchain based on proofs of space alone like Spacemint [PKF+18] could be secure under dynamic availability.

Surprisingly, the answer is a resounding no as shown in [BP22]. They consider a setting where the chain progresses in steps, where a step happens every time a new challenge is picked. The adversary can change the amount of space available to the honest parties by a factor with every step, and the space available to them is always a factor smaller than what the honest parties have. Moreover the space can be replotted in steps. Their result states that no matter what chain selection rule is used, in this setting a PoSpace based blockchain can always be successfully forked by an adversary with a fork of length at most steps. This bound is tight as a (albeit fairly complicated and thus not practical) chain selection rule achieving this bound exists.

6.2.4 Dynamic Availability from PoStake

The impossibility from [BP22] just discussed does not translate to proofs of stake based chain as there's no analogue for replotting in the stake setting. In fact, PoStake based longest-chain protocols secure under dynamic availability do exist [BGK+18]. The Ouroboros genesis chain selection rule from this paper works as follows: given two competing chains, one just compares the chains at a fairly short window right after the fork. Intuitively, the reason such a chain selection rule does not provide security under dynamic availability for space is because an adversary could use replotting to make this short window have large weight, thus create a winning chain even with much less space than the honest party.

Footnotes

-

If there's an epoch switch at some where the difficulty switches from to , let be the weighted average . ↩