1 - Introduction

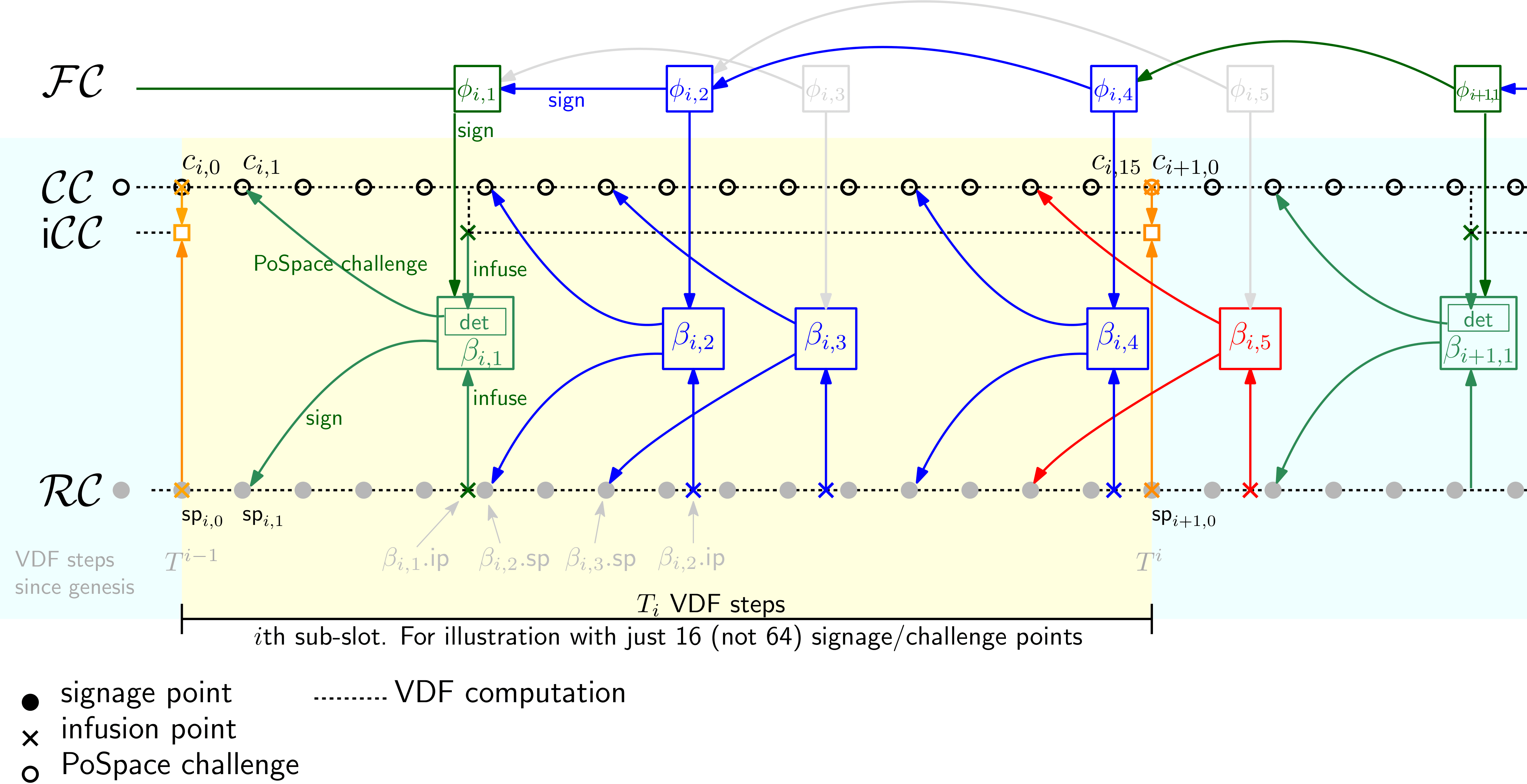

The network (chia.net) is a permissionless blockchain that was launched on March 19, 2021. is a "longest-chain" blockchain like Bitcoin, but uses disk-space instead of computation as the main resource to achieve consensus. This holds the promise of being much more ecologically and economically sustainable and more decentralized than a proof of work (PoW) based blockchain like Bitcoin could be. Figure 1 illustrates one slot of the blockchain. The main aim of this document is to explain the rationale for this rather complicated design.

As mentioned, is basically what's called a longest-chain protocol in the literature [BNPW19; BDK+19]. This notion captures blockchain protocols that borrow the main ideas from the Bitcoin blockchain: the parties (called miners in Bitcoin and farmers in Chia) that dedicate resources (hashing power in Bitcoin, disk space in Chia) towards securing the blockchain just need to

-

listen to the (P2P) network to learn about progress of the chain and to collect transactions.

-

locally use the resource (via proofs of work in Bitcoin or proofs of space in Chia) trying to create a block which extends the current chain.

-

if a winning block is found, gossip the new block to the network.

No other coordination or communication amongst the parties is required. In particular, as the miners in Bitcoin, the farmers in only need to speak up once they find a block and want it to be included in the chain.

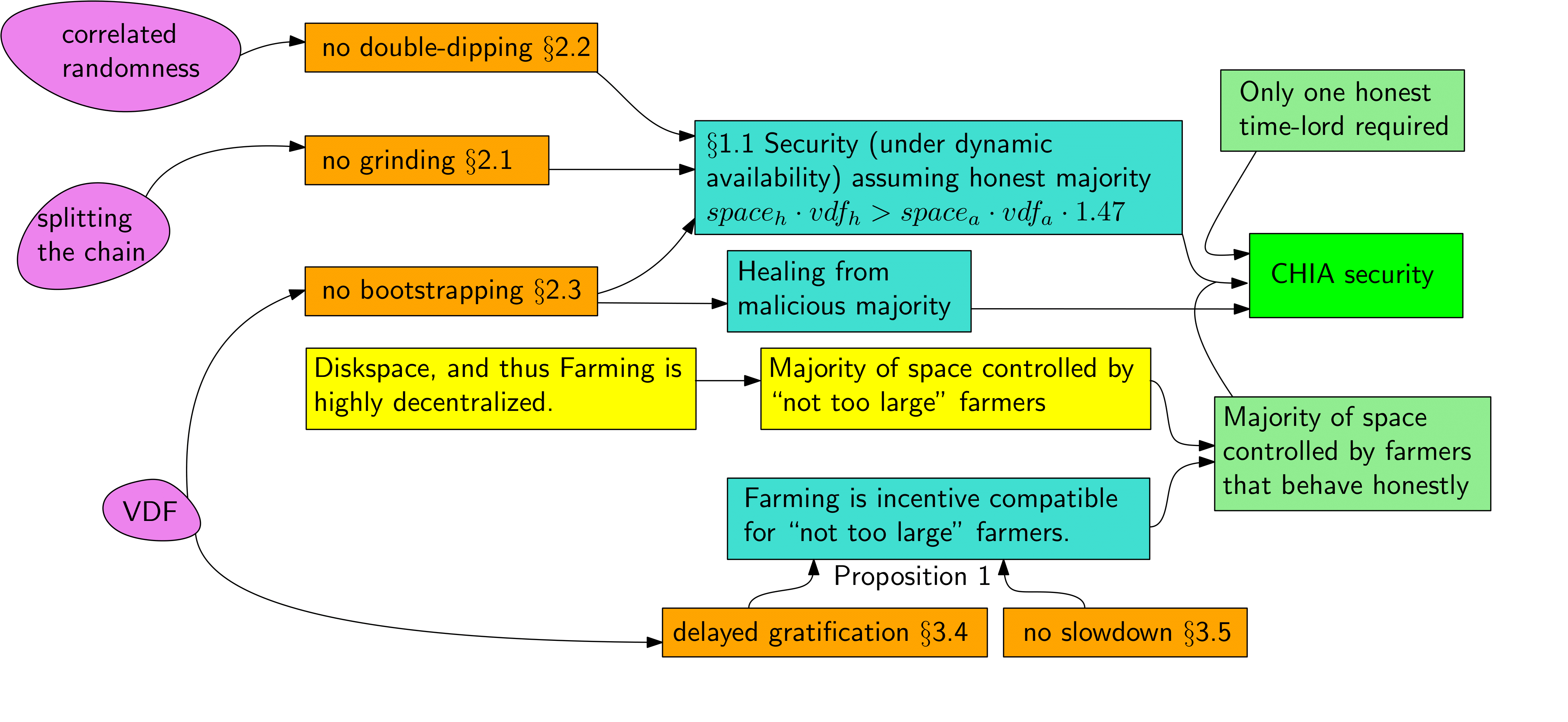

Constructing a secure permissionless blockchain using proofs of space is much more challenging than using proofs of work. In particular, a secure (under dynamic availability) longest-chain protocol based on proofs of space alone does not exist [BP22], so Chia's proofs of space and time (PoST) consensus protocol, apart from farmers providing disk space, additionally relies on so called timelords who evaluate verifiable delay functions (VDFs). Figure 2 gives an overview of the formal security proofs and more informal arguments outlined in this document.

1.1 Security

The Bitcoin blockchain is secure [GKL15] as long as the hashing power (measured in hashes per second) contributed by honest parties is larger than the hashing power available to an adversary, i.e.,

Similarly, the security of depends on the amount of space and controlled by the honest parties and the adversary, respectively. Additionally, the speed and (measured in steps per second) of the VDFs run by the fastest honest timelord and the adversary are relevant. With these definitions,

Let us stress that only requires a single timelord (which runs 3 VDFs) to be active at any time, in particular, in eq.(2) refers to the speed of the fastest VDFs controlled by an active and honest timelord, it doesn't matter if one or a billion timelords are active. In practice we'd still expect a small number – not just one – timelords to be available to have a backup should the currently fastest timelord become unavailable.

On the other hand, we make no assumptions about the number of VDFs controlled by the adversary. Security as in eq.(2) holds even when assuming the adversary controls an unbounded number of VDFs of speed .

This assumption comes at a price: there's a factor by which the adversarial resources are multiplied in eq.(2). This factor is there due to an attack we call "double dipping". This and other attacks will be discussed in §2. For now let us just mention that there's nothing special about the constant , it can be lowered to for any by increasing the number of blocks that depend on the same challenge (in this is set to at least 16).

The bound in eq.(1) is not tight in the sense that we don't have an attack that works if we replace "" with "". We have an attack assuming giving the adversary a slightly lower boosting factor of

More concretely, if , i.e., if the adversary has (an unbounded number of) VDFs of the same speed as the fastest honest timelord, then double spending is possible controlling of the total space.

A contribution of this writeup is a modular approach towards achieving secure longest-chain blockchains from efficient proof systems. In §2 we outline three attack vectors (illustrated in Figure 3) that emerge if we naïvely replace proof of work with an efficient proof systems.

1.2 Network Delays

In Bitcoin each block contains the hash of the previous block. If two blocks are found at roughly the same time, so there was no time for the block that was found first to propagate to the miner that found the second, they will refer to the same block, and only one can be added to the chain. The other will be "orphaned" and does not contribute towards securing the blockchain. The fraction of orphaned blocks depends on the network delay (the smaller the delay the fewer orphans) and the block-arrival time (fewer blocks per minute decrease the probability of orphans). Taking this into account, the security statement for Bitcoin from eq.(1) should be augmented to:

Even with its very slow 10 minutes block arrival time, Bitcoin's orphan rate was measured to be around [DW13]. As the chain is not a typical hash chain, but an ongoing VDF computation where blocks are infused, there's an elegant way to avoid orphans: the "infusion point" of a block is around seconds (more precisely, between and seconds) worth of VDF computations after the "signage point" it must refer to, and as long as the network delay is small enough so the block creating/gossiping process takes less than 30 seconds no orphans will occur. In particular, the bound from eq.(2) holds under this very weak network assumption independent of the block arrival time.

The target block arrival time in is set to seconds (32 blocks per 10 Minutes slot), and while each of those blocks contributes to security, only a subset of these blocks actually carry transactions (roughly , that's a block every seconds) in order to ensure that transaction blocks sequentially refer to each other. This prevents issues with inconsistent transactions, as each block producer knows the entire history.

1.3 Game Theoretic Aspects

Apart from proving security assuming the honest parties control a sufficient majority of the resources, to argue that a longest-chain protocol will be secure in the real world we need to justify why rational parties would behave honestly in the first place. In particular, it should not be possible to get more rewards by deviating from the honest mining/farming behavior. While Bitcoin is not fair in this sense due to selfish mining attacks [ES18], these attacks are not really practical and have not been observed in the wild for reasons we'll sketch below and discuss in more detail in §3.

Fairness in

Achieving fairness that is comparable to what Bitcoin achieves is a main design goal of . While arguing about fairness directly is rather subtle, we identify two clean properties called "no slowdown" and "delayed gratification" a longest-chain can satisfy. Delayed gratification by itself already is a deterrent against selfish farming, and we show (Proposition 1 in §3) that these two properties jointly imply a chain-quality (i.e., fraction of honest blocks in the longest chain) no worse that what Bitcoin achieves.

No-Slowdown

The no-slowdown property was identified as a desirable property for longest-chain blockchains in [CP19]. It holds if (even an unbounded) adversary cannot slow down the growth of the chain by participating. We discuss the no-slowdown in and various other chains in §3.5.

Delayed Gratification

The design ensures that proof of space challenges are only revealed once they are needed, and once they're revealed they cannot be influenced any more. This then implies that it's impossible for a selfish farmer to create more blocks by deviating from honest farming, and thus – like in Bitcoin – the only thing a selfish farmer can do is prevent other farmers from adding their fair share of blocks in the current epoch (potentially even losing out on blocks themself). The reason a selfish farmer would do this is in order to enforce a lower difficulty, and thus more rewards for themselves, in the future [ES18]. We denote chains with this property as having "delayed gratification".1 While delayed gratification doesn't prevent selfish mining, it severely limits the type of selfish mining possible, and we don't expect to observe selfish farming in for the same reasons we don't observe selfish mining in Bitcoin. As mentioned above, in combination with the no-slowdown property it even implies a chain-quality as in Bitcoin.

1.4 Farmers and Timelords

Constructing a secure blockchain based on proofs of space is significantly more challenging than with proof of work. So the design, as illustrated in Figure 1 is (arguably necessarily) more sophisticated than Bitcoin or other PoW based blockchains, which are basically just hash chains. Apart from proofs of space and standard cryptographic building blocks like hash functions and signature schemes, the security of crucially relies on verifiable delay functions (VDFs) [BBBF18; Pie19b; Wes20]. Informally, VDFs are functions whose computation is inherently sequential and verifiable and thus serve as a "proof of time".

We will now shortly sketch how the blockchain is maintained by farmers and timelords.

耕种

Farmers are the analog of miners in Bitcoin, but instead of hashing power, farmers contribute disk-space towards securing the blockchain. As in Bitcoin, they are incentivized by block-rewards and transaction fees. As in Bitcoin, the block-rewards (i.e., some freshly minted coins that go to the block creator) decrease over time, but unlike in Bitcoin they will never go to zero for reasons outlined in [CKWN16].

To participate in farming a farmer must first initalize its disk-space, this process is called plotting and the files created and stored during this process are called plots. The smallest allowed plot in is slightly larger than 100GB, though for plotting one temporarily needs more than this. Once the plot(s) are in place, a farmer just listens to the network for proof of space challenges. There's a new challenge roughly every seconds and they are computed by a timelord as discussed below. For efficiency reasons there's a "plot filter" which for each plot dismisses all but (in expectation) one in 512 challenges immediately, so a plot is only accessed once every 80 minutes. The reason to not increase this time even further are so called replotting attacks which we'll discuss in §1.8.3.

In only roughly of the blocks will carry transactions, but as a farmer doesn't know whether their block will be a transaction block when creating the block, farmers must always include transactions to the blocks they create.

Timelords

A timelord runs three VDFs, once every seconds they gossip a "signage point" that serves as a PoSpace challenge for the farmers. They also listen to the network for blocks created by farmers. If a valid block is received in time it gets "infused" into the chain (the infusion is always somewhere from to seconds after the signage point).

The above only holds for the the timelord which runs the fastest VDFs. Timelords with slower VDFs can basically just recompute values that were already gossiped, so there's seemingly no point for them to participate. We still want a small number of timelords to participate (or at least be ready to take over) should the fastest timelord fail or misbehave.

Unlike farmers, timelords do not receive any rewards in form of block-rewards or transaction fees. One reason is technical, unlike for farmers whose PoSpace contained in the blocks are linked to a signature public-key to which a reward can be given, the computation of the timelords is (and to prevent grinding attacks must be) canonical, they cannot attach a public-key to the values they computed. A second reason is the fact that it's not clear at all how such a reward would be distributed. If the fastest timelord gets the entire reward only they would be incentivized, but not the slower ones we'd like to have as back-ups. If also the slower ones get something then we'd get a PoW type lottery which we want to avoid in the first place. thus relies on a small number of timelords to run fast VDFs without being incentivised by on-chain rewards.

1.5 Difficulty and Chain Selection Rule

Difficulty

In Bitcoin a difficulty parameter controls how many hashes are required in expectation to find a block. This parameter is re-calibrated every 2016 blocks (called an epoch and taking roughly 2 weeks) so blocks arrive roughly every 10 Minutes.

has two parameters, a difficulty parameter and a time parameter , these are re-calibrated once every blocks (this epoch takes around 1 day). The time parameter is reset to fit the target time of 10 minutes per slot, while the difficulty is reset to target an average of 32 blocks per slot.

For example if in an epoch the amount of space is higher than anticipated the difficulty for the next epoch would get up while the time parameter remains unchanged . If the VDF speed in the epoch is higher than anticipated (i.e., the epoch only takes instead of hours) the time parameter goes up , and even though the space didn't change, the difficulty needs also to go up account for the fact that now an epoch has more VDF steps.

Chain Selection Rule

Bitcoin has a very simple chain selection rule (aka. fork choice rule) which specifies which fork a miner should work on: a miner should always try to extend the "heaviest" chain they are aware of. The weight of a chain is the sum of the blocks, each multiplied by the difficulty parameter used while it was mined. Unless we consider forks which pass an epoch boundary, the heaviest chain is also the chain with the larger number of blocks, hence the name "longest chain" protocol.

We can define the weight of a chain in analogously to Bitcoin, and currently the default farmer code follows basically the same "follow the heaviest chain" rule as Bitcoin miners. But let us stress that it's not clear whether for this simple rule is the best choice. For example, one could consider a rule for farmers where in case of a fork where both chains have the same weight they would work on both chains (note that in a PoW based chain this is not possible). While such a rule can slow down consensus, the observed fork could be due to an attack (double spending or selfish mining) trying to "split" the contribution of the honest space in two different chains, letting the farmers work on both forks would thwart this.

In we also must specify a chain selection rule for the timelords. A timelord who does not control the fastest VDF will constantly fall behind and thus intuitively should just constantly adapt the chain with the most VDF steps in them. But if all timelords naïvely do this a malicious timelord controlling the fastest VDF could simply skip infusing any blocks they want, allowing for all kinds of attacks. Thus the rule for timelords has to be more nuanced, taking into account the chains they observe, and also blocks that were created by farmers but not infused in any of the chains.

Determining the best rules for farmers and timelords is ongoing research. Fortunately, the rules for farmers and timelords are more of a social convention rather than a specification of the chain. As our understanding improves, new rules can be implemented in the code base and there's no need for a (soft) fork.

1.6 Cryptographic Building Blocks

The blockchain uses standard cryptographic building blocks, in particular hash functions and signature schemes. More interestingly, it relies on two (non-interactive) proof systems which were especially developed for constructing sustainable blockchains: proofs of space and verifiable delay functions. We shortly discuss the requirements has to these building blocks.

Hash Functions.

uses SHA256 for hashing, but any collision resistant hash function would do. For efficiency reasons, we also use the round function of CHACHA8 and BLAKE3 within the proof of space construction where we just need some scrambling but no cryptographic hardness (not even one-wayness).

Signatures.

uses deterministic BLS signatures for signing. In principle any signature scheme could be used as long as the signatures are unique, i.e., it's impossible (or at least computationally hard) to create two different valid signatures for the same message. Uniqueness will be crucial to prevent so called grinding attacks.

Verifiable Delay Functions.

A VDF is specified by some inherently sequential function, and a proof system for showing the output of the function is correct. The sequential function used in the VDF deployed in is repeated squaring in class groups of unknown order. The group is not fixed, but a fresh group is sampled every time a value is infused. The proof system is Wesolowski's [Wes20] proof of exponentiation which has proof of size only one group element. Only the VDF output, but not the proofs, are committed on-chain. This has the advantage that one can replace the proofs. In the current implementation one first computes a much larger but faster to compute proof of 64 group elements, which later is replaced by a normal (one element) Wesolowski proof. It also means one can easily replace Wesolowski's proof with another proof system should a weakness with this proof system (which relies on new number theoretic assumptions) be discovered. We discuss VDFs in detail in §A.3.

Proofs of Space.

The notion of proofs of space was introduced, and a first construction proposed, in [DFKP15] (a security proof for their construction in the random oracle model was given in [Pie19a]). This construction, which is combinatorial and based on pebbling lower bounds for particular graphs, has the major drawback that the initialization phase is interactive. A consequence of this is that if one wants to use this PoSpace in a blockchain, the farmers must first commit to their plots before they can be used for farming (say by recording this commitment on-chain via a special transaction as suggested in Spacemint [PKF+18]). A new PoSpace with a non-interactive initialization had to be developed for [AAC+17]. This construction basically just specifies some function , and then stores its function table sorted by the outputs . On challenge some value , the prover looks up the entry (which is efficient as the list is sorted) and replies with the proof , which can be easily verified checking that . Unfortunately this simple construction miserably fails to be secure: the prover can store much less than the full function table, while still being able to efficiently find proofs. The reason are Hellman's time-memory trade-offs, a technique proposed in 1980 to break symmetric cryptographic schemes [Hel80]. In [AAC+17] it is shown how this simple construction can be "salvaged" to overcome any time-memory trade-offs.2 We'll discuss definition of a PoSpace, and the construction used in in particular, in §A.2.

1.7 A High Level View of the Protocol

The design and rationale of the blockchain is explained in the following sections, here we'll just give a very high level view of the chain as illustrated in Figure 1. The chain itself consists of four chains, one hash chain and three VDF chains.

Hash and VDF chains

While hash chains are a classical cryptographic construction, VDF chains were first used in . A VDF chain alternates VDF computations with infused values. It provides the security properties present in hash-chains, that is, the head of a chain commits its entire past (technically, given the head of a hash or VDF chain, it's computationally infeasible to come up with two different chains that end in that value). In addition, VDF chains come with a sequentiality property: the number of sequential steps to compute the VDF chain is the sum of the steps required for all the VDFs in that chain, i.e., the VDFs must be computed sequentially. Hash and VDF chains are discussed in more detail in §4.

The four chains which constitute the blockchain are the (1) foliage chain , which is a normal hash-chain and contains the transactions (2) the reward chain which records all blocks (3) the challenge chain used to create PoSpace challenges and (4) the infused challenge chain for some extra security properties. While and are normal VDF chains, is more of a sequence of forks from .

Blocks

A block is made of two parts, the foliage block , which contains the payload (transactions and a time-stamp) and the trunk block which contains a PoSpace and a signature .

Building the Chains

-

A timelord computes the chains and broadcasts relevant values to the network. This includes signage points and which are the values of the and chains (together with a proof that these values are on the VDF chains) once every seconds.

-

A farmer who receives these signage points and checks whether these points are of interest (i.e., on the heaviest known chain) and all the VDF proofs verify. Next, for each of their plots, they use as a challenge to compute a PoSpace . Then they check whether satisfies a winning condition that allows to produce a block.

If a winning PoSpace is found, the farmer creates a signature of (that verifies under the associated with ) and a foliage block and then gossips the block .

-

When a timelord receives this block, they check whether the block satisfies all conditions to be infused into the chain.

() If yes, the trunk block is infused into once its infusion point is reached, which is somewhere between 3 and 4 signage points (28.125 to 37.5 seconds worth of VDF computations) past the signage point of that block.

() If this happens to be the first block whose signage points are in the current slot, then (but not ) is infused into the challenge chain at the end of the current slot. This way the challenge chain depends only on one block per slot.

() For some extra security, the timelord doesn't simply wait till the end of the slot to infuse the signature, but a third VDF is used to fork from at the infusion point by infusing into , and this fork, called the infused challenge chain , is then infused back to at the end of the slot.

() If the signage point of this block is later than the infusion point of the last transaction block, then this block is also a transaction block. Only in this case its foliage is appended to the foliage (hash) chain , and this block becomes a "transaction block".

1.8 Space Oddities

When constructing a proof of stake or proof or a space based longest-chain protocol one faces similar challenges due to "nothing at stake" (aka. costless simulation) issues, we'll discuss these in §2. But there also aspects in which Space and Stake differ, and we'll shortly discuss three of them below. The first difference is the fact that space, unlike stake, is an unsized resource, which for example means that we can't have "certificates" [LR21]. The second difference is the fact that stake is an internal resource, while space is an external resource, one of the consequences of this is that a space based protocol can recover from malicious majority, while a stake based cannot. The third are replotting attacks against space which have no analogue in the stake setting.

1.8.1 Sized vs. Unsized

A key difference between stake and work is the fact that in a stake based chain we know the amount of the resource available for mining, while for an external resource like work or space this is no longer the case. Lewis-Pye and Roughgarden [Lew21; LR21] formalize this as the sized vs. unsized setting and prove some fundamental differences between them. The main result in [LR21] shows that certificates which "provide incontrovertible proof of block confirmation", only exist in the sized setting, i.e., for PoStake but not PoWork blockchains.

In their framework space and also space and time (i.e., the available space multiplied with the speed of the available VDFs) as used in are an unsized resource, so we can't hope to get certificates.

1.8.2 Internal vs. External

Work or space are actual resources and we can unambiguous talk about some party holding some amount of the resource at some given point in time. Stake on the other hand is an internal resource defined relative to some chain on which it is recorded and "holding some stake" usually refers to the stake a party controls on the chain that currently is considered the valid one by honest parties.

The main advantage on using stake to secure a longest-chain protocol is the fact that it's extremely sustainable as no external resource is required to secure the chain. But this comes at a price, one common argument against stake is that the chain is not really permissionless as participating in mining requires acquiring stake from the parties currently controlling it. Also from a security perspective an internal resource is delicate as keys controlling stake not on the current chain can be used to attack the chain. A simple example would be an attack by which a party acquires keys that were valid at some block in the past, but which are no longer valid at the current block and thus are "cheap" (e.g., the party can lend a large amount of stake for a short time, or offer to buy outdated keys), and then uses these keys to fork at block and bootstrap a chain to the present.

To prevent such attacks some chain require parties to delete old keys, but it's irrational for a party to delete old keys if they can be valuable in the future, say because one can sell them to an attacker (and this is rational if one holds just little stake, so not selling is unlikely to prevent the attack) or because there's a deep reorg and the old keys suddenly become valuable again. Combining stake with VDFs would make such attacks harder, but not prevent them as we'll discuss in §6

1.8.3 Replotting

A subtle but important difference between stake and space is the fact that space allows for replotting which has no analogue in the stake setting: Given a challenge , a space farmer controlling a plot of size can efficiently compute one proof . This is analogous to the stake based setting, but unlike in the stake setting, the farmer can inefficiently compute multiple proofs for challenge by repeatedly creating fresh plots and computing one proof with each of them.

We refer to attacks exploiting this fact as replotting attacks. The most basic design choice to harden a chain against replotting attacks is to make sure that challenges arrive at a sufficiently high rate so that substantial replotting in-between two challenges is not feasible. Moreover the plot filter (which dictates what fraction of plots must be accessed with every challenge) cannot be chosen too aggressively as more aggressive filters makes potential replotting attacks easier.

A fundamental fact about PoSpace that crucially relies on replotting is that no PoSpace based longest-chain protocol secure under dynamic availability exists [BP22], we'll discuss their result in more detail in §6.2.3. overcomes this no-go theorem by using VDFs, we discuss security under dynamic availability and healing from malicious majority in the work, stake and space setting in §6.