Intro to Cryptocurrencies

What is a Cryptocurrency?

A cryptocurrency system can be thought of as a payments and financial infrastructure that is not controlled by any single entity, such as a bank, company, or government. Prior to the introduction of cryptocurrencies, there had always been an operator that had control of transaction inclusion and monetary policy. This operator represented a centralized point of both power and failure.

The financial world was fundamentally changed with the introduction of Bitcoin on January 3, 2009. In the years that have followed, many other cryptocurrencies have been created to solve various problems in the legacy financial realm.

Cryptocurrencies use clever cryptography, mathematics, and monetary incentives to create a system where people called farmers or miners get paid to run the system, and there is no central point of control that can be taken down by malicious actors.

This brings many benefits, some of which are:

- No requirements to participate: Anyone with an internet connection can participate in the new crypto economy, regardless of nationality, wealth status, religion, etc.

- Censorship resistance: Censorship is difficult or impossible. Anyone is allowed to transact, and to send any amount or run any program at any time.

- Independent monetary policy: New currencies can be created that do not depend on decisions made by one group or one country, and instead can be based on algorithms or have a fixed supply.

- Unstoppable applications: A program developed for, and run on, a secure blockchain can never be changed or stopped. The program itself can own funds and perform financial transactions. Code can run autonomously, without depending on a human operator. Some blockchain applications include: tokenization of other assets, non-fungible tokens (NFTs), loans, remittances, identity wallets, etc.

- Global standards: Through crypto, different countries and regions can interact and transact on one shared standard that is clearly documented, fully open source, and available for free. Different parties can come together to use a neutral platform, which reduces costs for those who build on top of the cryptocurrency.

- Security: There are many forms of potential attacks on any financial infrastructure, including virtual and physical hacks, bribery, network issues, etc. A system with a million nodes is much more difficult to attack than the aforementioned single point of failure.

How do Cryptocurrencies Work?

To understand the basics of how a cryptocurrency like Bitcoin or Chia works, we first need to look at how one would design a cryptocurrency from scratch. This section is targeted toward those new to the blockchain industry; others can skip it.

For a deeper introduction we recommend the book Bitcoin and Cryptocurrency Technologies which also has a freely available pre-print and video lectures.

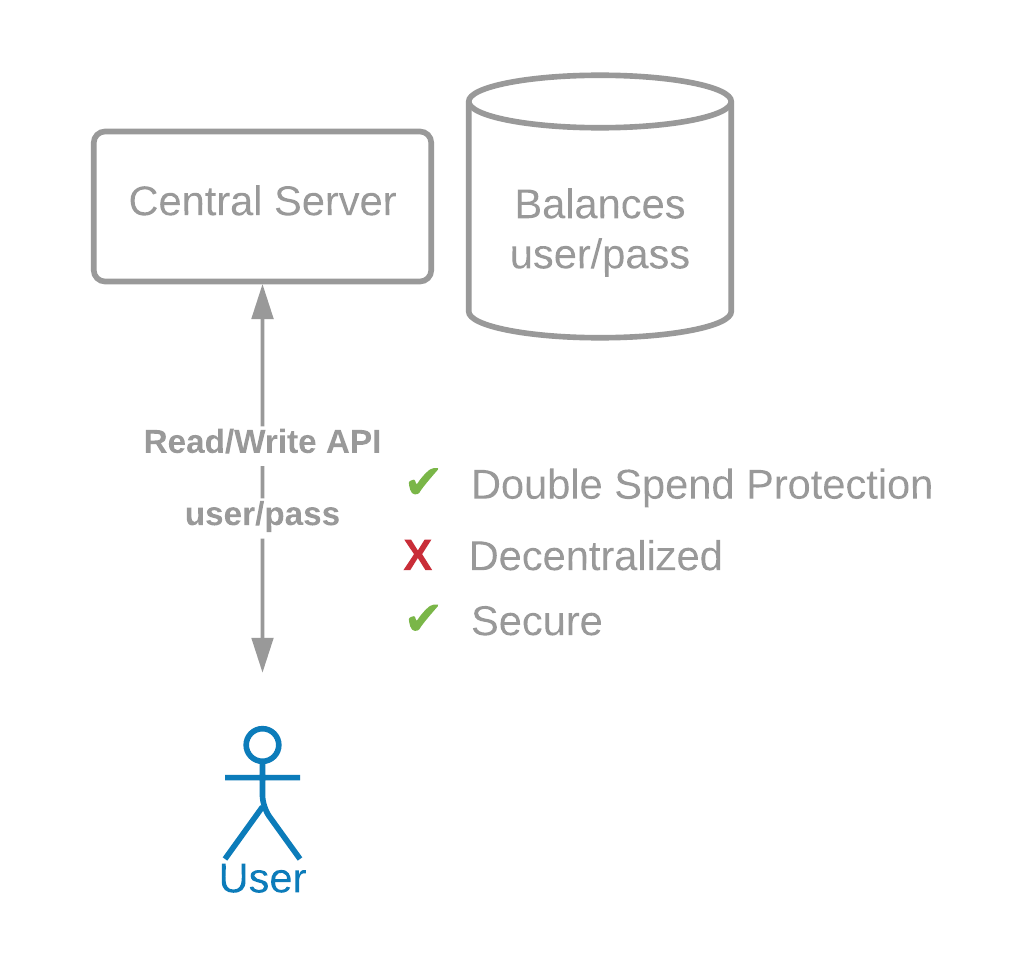

We could rely on a central server with a public API to send transactions (which takes in a username and password) and a public API for reading data. However, this is not decentralized, and it does not bring most of the benefits above. This is the way in which many financial systems worked before Bitcoin.

How would we design a transaction system which does not depend on any one party?

Authentication

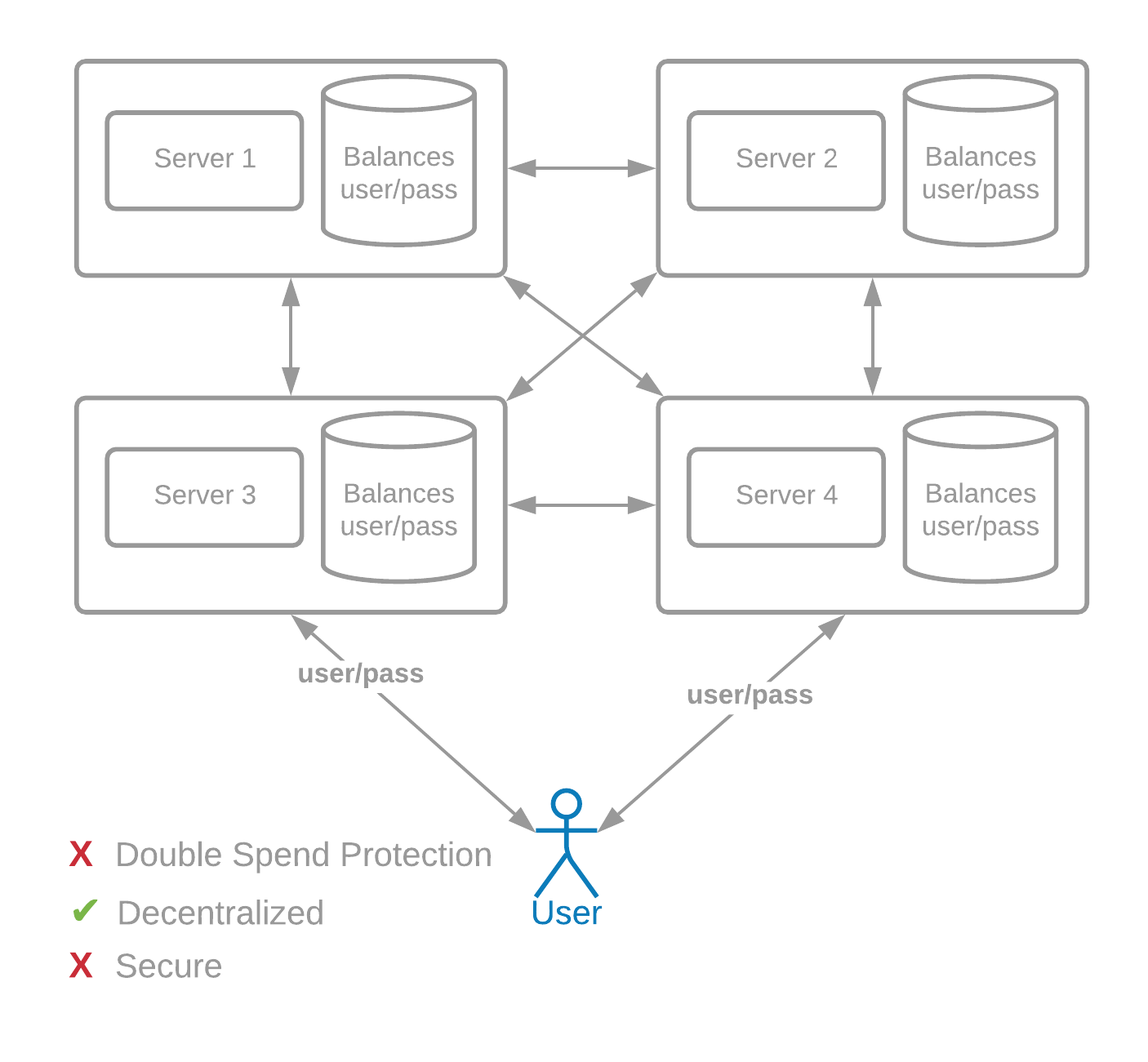

First, we need a secure way to send transactions to many servers. Let's assume that there are 1000 servers across the world, instead of just one, and that these servers send transaction information of users to each other.

These servers are assumed to be run by different entities (companies, people, etc). Usernames and passwords would not work in this decentralized model, because every server would need to know the password in order to verify that a transaction is valid. This would be extremely insecure.

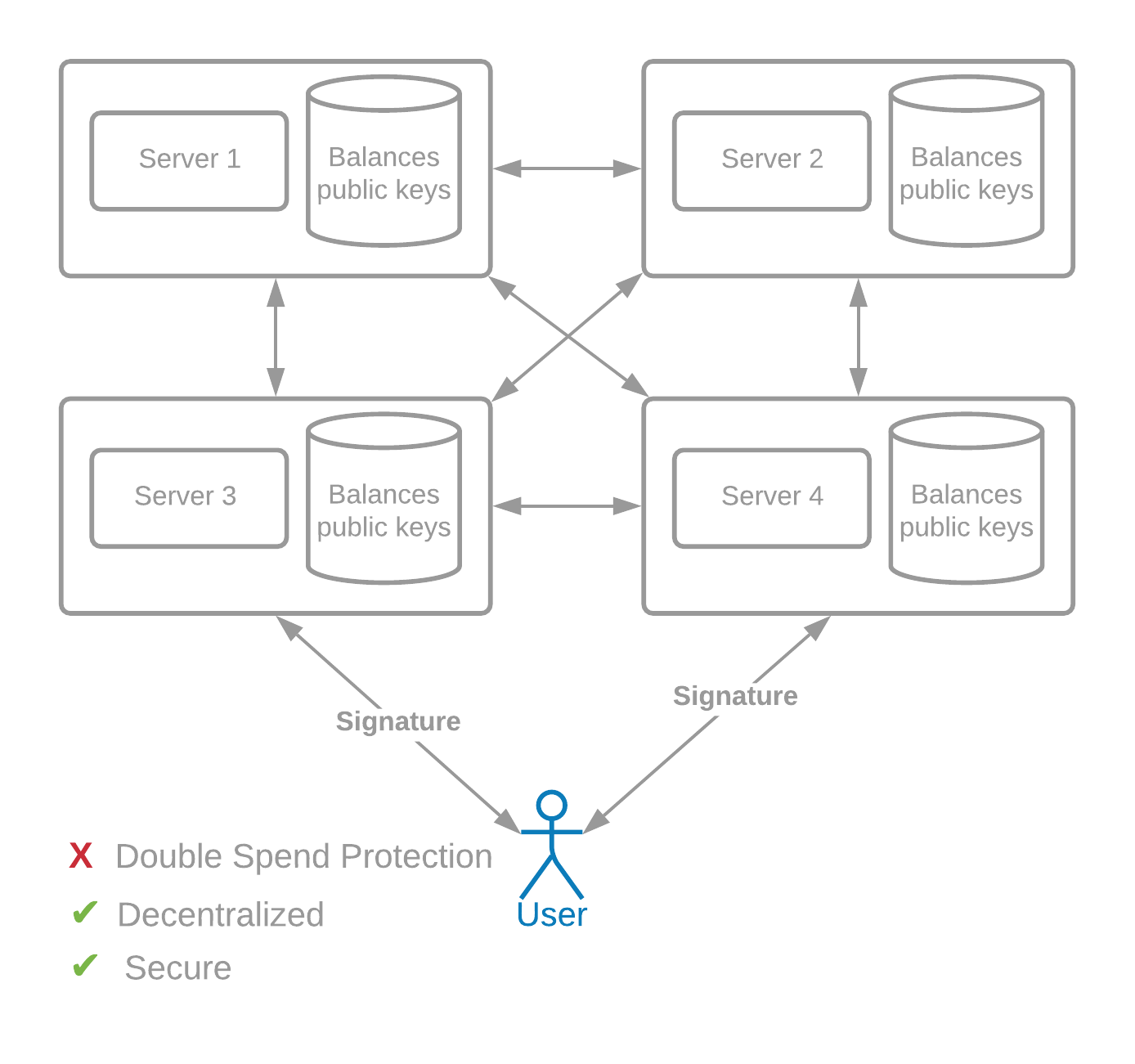

Instead, we can use public key cryptography, invented by Hellman, Merkle, and Diffie.

For example, a user named Alice maintains a secret key (also called a private key) sk_a, and a public key pk_a. The public key is posted in a transaction next to her balance, let's say 1 BTC. In order to spend that 1 BTC, she needs to provide a digital signature with her private key. The signature can be verified with the public key and message only, and is specific to the data that is being signed.

Each server running in this decentralized system can accept a transaction, which includes the ID of the coin that is being sent, the recipient information, and the signature.

Digital signatures are fundamental building blocks for cryptocurrencies.

Double Spending

However, signatures are not enough, because of an issue called the "double spend problem." Of the 1000 servers, let's say 500 are in Asia and 500 are in America. An attacker, Bob, sends two transactions that spend the same coin, to two servers, at the same time: one in Asia and one in America. Those transactions send the money to different recipients, which should not be allowed.

In this case, the two servers need to come to agreement as to which transaction came first. Otherwise, they will have diverging state, and the system will not have global consensus. To solve this issue, we need a consensus algorithm, or a way for all computers in the system to quickly come to unambiguous agreement on the ordering and content of transactions.

Since we are trying to create a globally decentralized and secure system, why not allow each person one vote, and add up votes for deciding transaction ordering? This would be great if it were possible, but it unfortunately requires some type of central party, first to decide who is a "person," and then to create these identities. This would make the system centralized.

We could instead base the system on "one computer, one vote," counting each IP address as a "computer." However, it is trivial to buy new IP addresses, or to change addresses using a VPN or a proxy server. An attacker could even create millions of fake IP addresses. The attacker would gain control of the network once they own 51% of the addresses. At this point, they could decide transaction ordering and content. Again, the system becomes centralized, and possibly compromised.

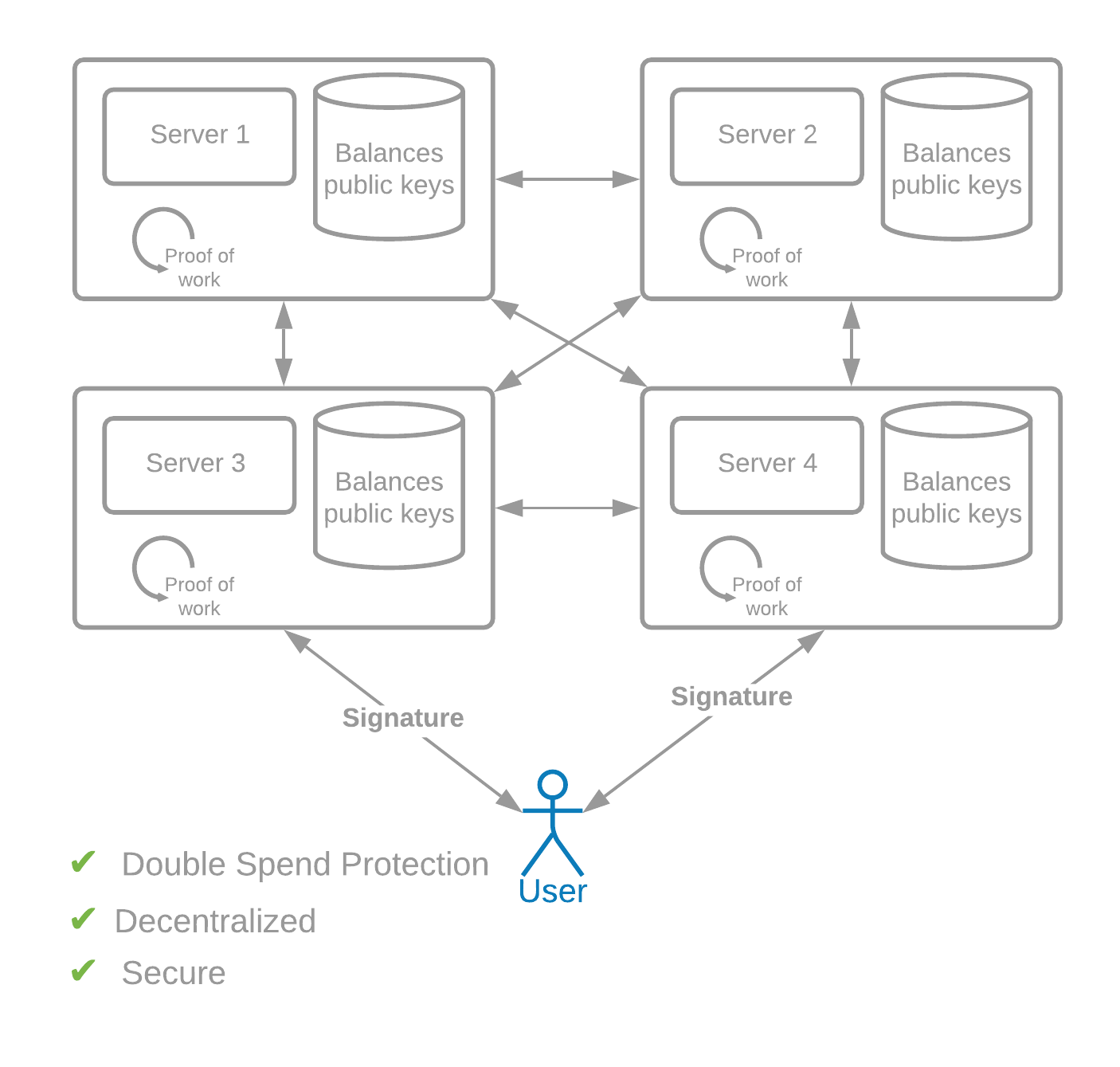

The key issue that makes it difficult to solve the double-spend problem is the Sybil attack. A Sybil attack is when an attacker creates a large amount of fake identities at a low cost. Most "Proof of X" blockchains are not secure because if an attacker creates multiple identities, this will give the attacker an advantage.

The genius of Satoshi Nakamoto was to solve the double-spend problem by requiring real-world work in order to obtain "votes," and to decide consensus. This "Proof of Work" is cryptographically verifiable. The only requirements for participation are a computer and an internet connection.

In Proof of Work networks, each computer that is participating repeatedly generates cryptographic hashes using random input. This functions as a global lottery, where hashes are generated until one computer generates a winner -- a hash with a certain number of leading zeros. This is known as a proof of work because there are no shortcuts. Computers must put in the required amount of computational "work" by generating hashes.

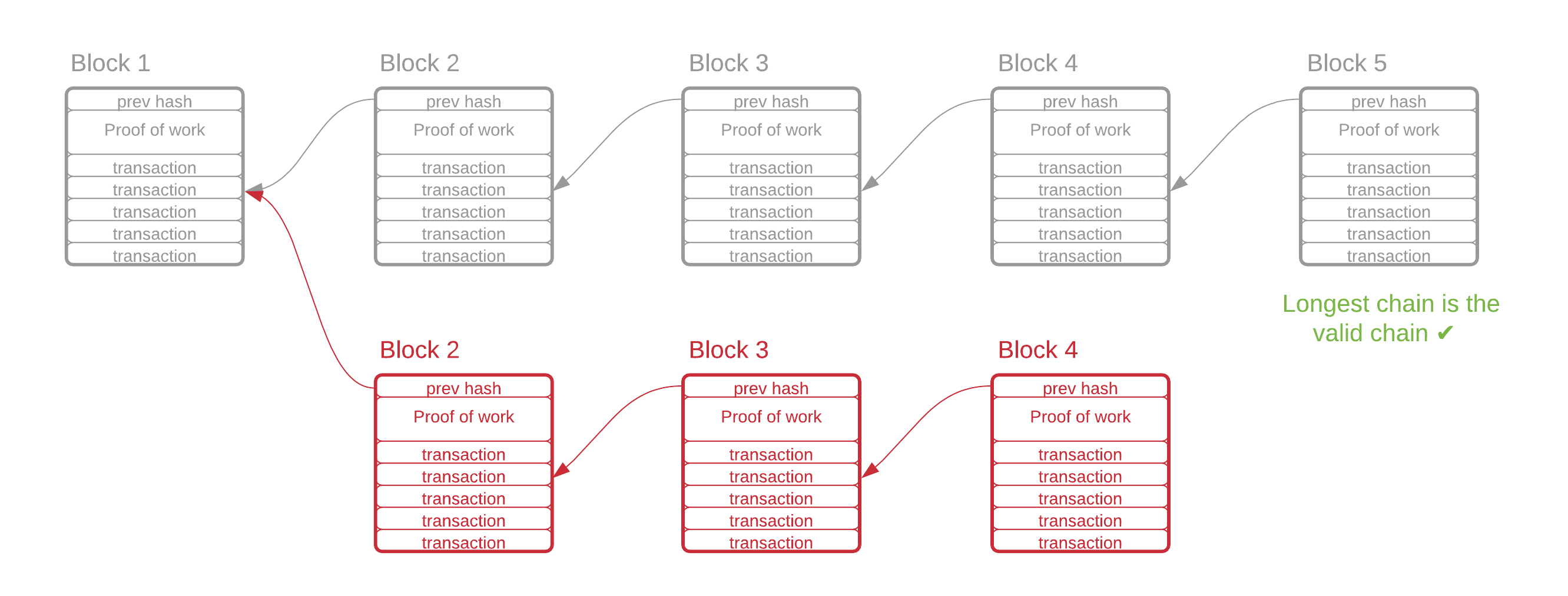

When a winning proof is found, the computer that discovered it earns the right to generate a new "block" in the blockchain. This block contains a pointer to the previous block, a list of valid transactions, and the winning hash. All nodes are required to accept the heaviest chain (the one which required the most work). Therefore, all nodes will accept the new block, and the proof-of-work lottery begins anew.

In Bitcoin's consensus algorithm, each proof takes an average of 10 minutes to generate. As more computers join the network, the average amount of time to generate a proof will naturally decrease. This brings us to another of Satoshi's simple and elegant ideas: the difficulty adjustment. Every 2016 blocks (two weeks, on average) the proof-of-work algorithm automatically adjusts how difficult it is to find a proof. It accomplishes this by increasing or decreasing the required number of leading zeros in a generated hash. The result is that the average time required to find a proof will always be 10 minutes, no matter how many computers start or stop participating in the proof-of-work lottery.

With this consensus mechanism in place, attacking the network becomes very difficult. If an attacker wants to "rewrite history" by creating an alternative blockchain, they'll need to create new blocks faster than the honest actors in the system. Because of the proof of work that is required to create each block, the attacker will need to generate hashes faster than all other computers in the network, combined. This is known as a "51% attack" and is discussed in greater detail later in the Consensus Attacks page.

Proof of Work solves the double-spend problem -- only one computer can create a block at any one time. It also solves the Sybil problem -- not only does creating a block require a real-world investment in hardware, but it also gives no advantage to someone who creates multiple identities. This person has the same probability of winning, whether they're using one identity or a million.

Blockchain

Each node in the network maintains active connections with a few other random nodes. If a user wants to make a transaction, they send it to any node in the network, which automatically broadcasts it to their peers. Because each node is connected to a unique set of peers, the transaction quickly gets propagated to every node in the network. The nodes then save the transaction, including all other pending transactions, locally in memory. This is called the mempool.

For more info on Chia's mempool, see the Mempool page.

In order for each node to search for a proof, it must assemble a block to hash against. It does this by including transactions from the mempool, and it will most likely choose the pending transactions that pay the highest fee. A transaction fee market is thus created, where the supply is the total transactions per second (TPS) that the system supports, and the demand is based on the number of transactions in the mempool. A transaction is said to be "confirmed" once it is included inside a block which has the required proof of work.

Blockchain transactions can also include scripts or programs, which allow controlling funds directly with code. This code can require a certain number of signatures to release the funds, or have any arbitrary logic.

Keep in mind that blockchain programs are expensive to run, since every node in the system must download and run the program. Just because it can be run on a blockchain, doesn't mean that is should be run on one.

Each block also has a hash pointer to the previous block. This means that the hash of the contents of the previous block are included in the current block. If an attacker could find an alternative valid proof for a historical block, the proof would then change that block's hash, which would invalidate the next block. If the attacker wanted to change a block that occurred 10 blocks in the past, they would therefore need to re-do the proof of work for at least 10 blocks. The rest of the network would continue to create legitimate blocks, however, so in reality, the attacker would likely have to create many more than just 10 blocks. In fact, as long as the rest of the network, combined, could create blocks at the same rate or faster, the attacker would never be able to create a chain longer than the legitimate chain.

The Bitcoin network performs around 170 quintillion (170,000,000,000,000,000,000) hashes per second; the attacker would have to control at least that much hashpower to make a 51% attack feasible.

Beyond Proof of Work

Over a decade has passed since the creation of Bitcoin and Proof of Work blockchains. While Proof of Work is quite secure, that security comes at a cost: a tremendous expenditure of energy is required to generate those 170 quintillion hashes per second. On top of that, specialized hardware is required to run nodes on these systems, which has led to a high degree of centralization among the top miners.

Perhaps most troubling of all are the pools. On a given day, the hashrate of the top four or five Bitcoin pools constitutes over half of the overall hashrate. Arguably, the easiest attack against the Bitcoin network would be for the pool operators to collude (either willingly or under threat), putting a 51% attack well within reach.

These issues have prompted people to develop alternative Sybil-resistant consensus models. Proof of Stake (voting with blockchain assets) is one of the most popular approaches, and within this category there are many types of algorithms. These systems tend to compromise on decentralization (and thus, security) to varying degrees.

Chia takes an alternate approach called Proofs of Space and Time (PoST), which we think is likely to be more decentralized and accessible than Proof of Stake. In this model, full nodes store files full of millions of hashes (akin to lottery tickets, as described above) on hard drives. This model maintains the security properties of Nakamoto's Proof of Work, while remaining accessible to normal users without any special hardware.