Proof of Space

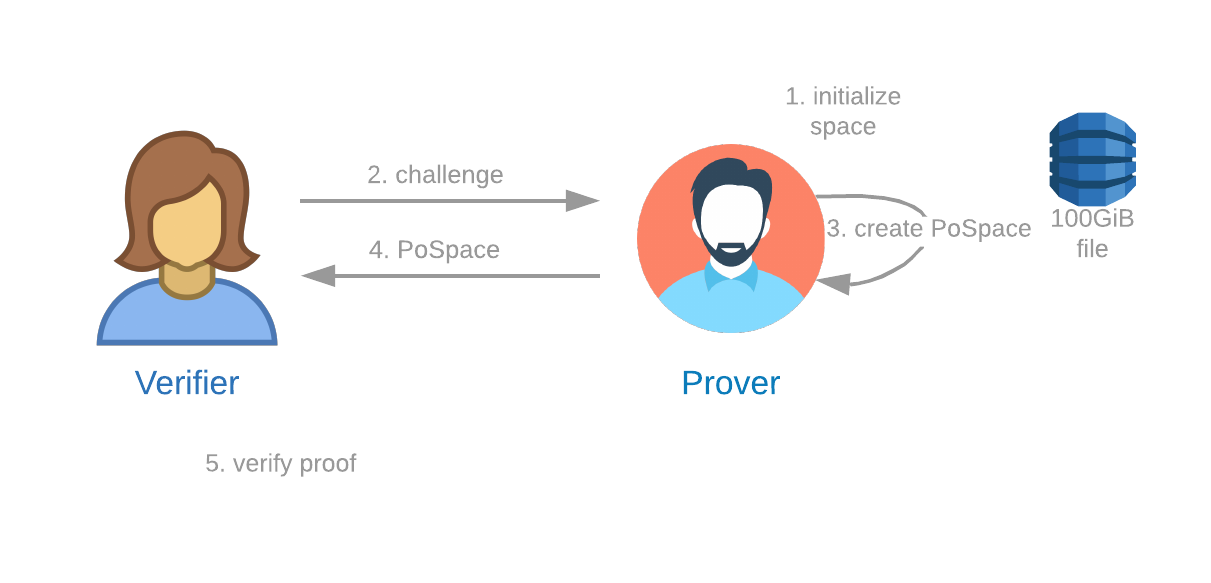

A Proof of Space protocol is one in which:

- A Verifier can send a challenge to a Prover.

- The Prover can demonstrate to the Verifier that the Prover is reserving a specific amount of storage space at that precise time.

The Proof of Space protocol has three components: plotting, proving/farming, and verifying. For more info, see our Details of the chiapos specification, and reference implementation.

Plotting

Plotting is the process by which a Prover, who we refer to as a farmer, initializes a certain amount of space. To become a farmer, one must have at least 101.4 GiB available to reserve on their computer (the minimum spec is a Raspberry Pi 4). There is no upper limit to the size of a Chia farm. Several farmers have multi-PiB farms.

As of Chia 1.2.7, a k32 plot can be created in around five minutes with a high-end machine with 400 GiB of RAM, or six hours with a normal commodity machine, or 12 hours with a slow machine using one CPU core and a few GB of RAM. Opportunities still remain for huge speedups. Furthermore, each plot only needs to be created once; a farmer can farm with the same plots for many years.

Plot sizes are determined by a k parameter, where space = 780 * k * pow(2, k - 10), with a minimum k of 32 (101.4 GiB). The Proof of Space construction is based on Beyond Hellman, but it is nested six times (thereby creating seven tables), and it contains other heuristics to make it practical.

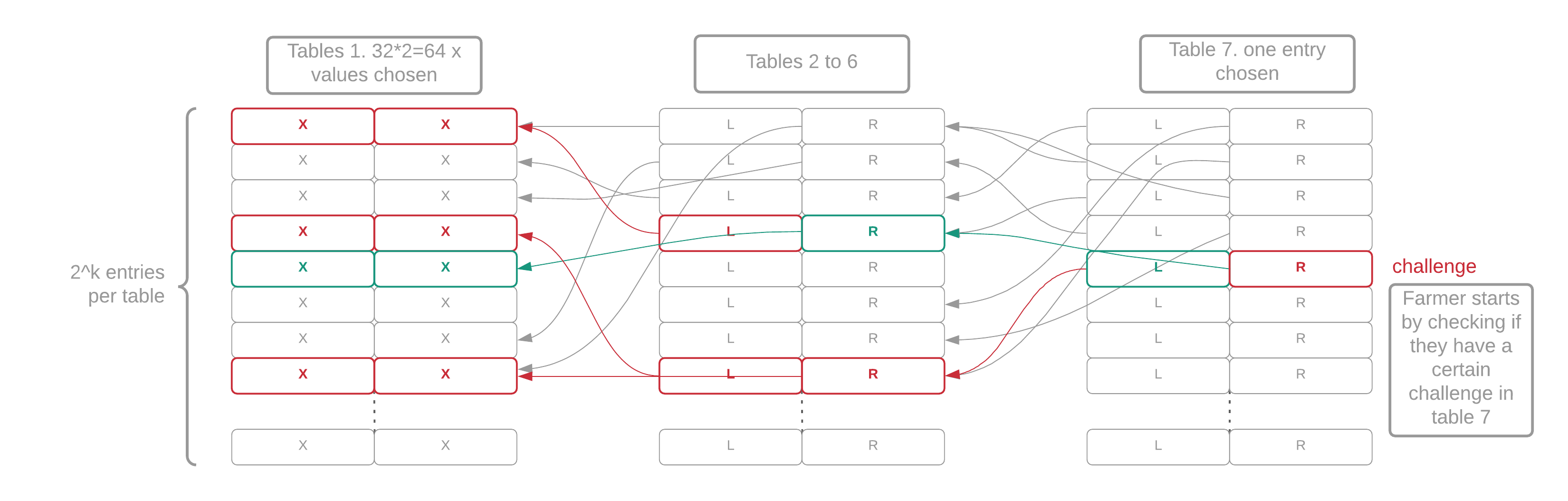

Each of the seven tables in a plot is filled with random-looking data that cannot be compressed. Each table has 2^k entries. Each entry in table i contains two pointers to table i-1 (the previous table). Finally, each table-1 entry contains a pair of integers between 0 and 2^k, called "x-values." A proof of space is a collection of 64 x-values that have a certain mathematical relationship. The actual on-disk structure and the algorithm required to generate it are quite complicated, but this is the general idea.

Figure 2: Structure of a plot file. The 64 red x-values represent the proof, the 2 green x-values represent the quality.

Once the Prover has initialized 101.4 GiB, they are ready to receive a challenge and create a proof. One attractive property of this scheme is that it is non-interactive unless the farmer chooses plot NFT style pooling: no registration or online connection is required to create a plot using the original plot format. Nothing hits the blockchain until a reward is won, similar to PoW. For pool portable plots, a farmer only needs a few mojos to create a plot NFT before plotting and then everything has the same characteristics from there.

See the Plotting FAQ page for more info.

Farming

Farming is the process by which a farmer receives a sequence of 256-bit challenges to prove that they have legitimately put aside a defined amount of storage. In response to each challenge, the farmer checks their plots, generates a proof, and submits any winning proofs to the network for verification.

For each eligible plot (explained later), a farmer uses the following procedure to generate a full proof of space. Keep in mind that a plot consists of 7 tables (T1-T7) of approximately the same size, as well as 3 checkpoint tables (C1-C3), which are much smaller:

- The farmer receives a challenge from the VDF

- For each eligible plot, extract a k-sized value from the challenge, where k denotes the size of the plot (k32, k33, etc)

- Look in the C2 table for a location at which to start scanning the C1 table

- Scan the C1 table for the location at which to start scanning the C3 table

- Read either one or two C3 parks. The number of parks to read depends on the index and value calculated from the C1 table. This requires an average of 5000 reads (the maximum is 10 000). These are sequential reads of 4 bytes (for an average total of 20 KiB)

- Grab all the f7 entries matching the challenge value (which can be 0 or more), along with the index in the table at which they were found

- For each matching f7 value, read T7 at the same index where the f7 value was found in its own table, and grab that entry, which is an index into T6

- The T6 index contains one line point with two back pointers to T5, four to T4, eight to T3, sixteen to T2 and thirty-two to T1. Each back pointer requires 1 read, so a total of 64 disk reads (1 index from T7, 63 back pointers) are performed to fetch the whole tree of 64 x-values.

Since most proofs generated by this process are not good enough (as discussed in the Signage and Infusion Points page) to be submitted to the network for verification, we can optimize this process by only checking one branch of the tree. This branch will return two of the 64 x-values. The position of the x-values will always be consecutive and will depend on the signage point (eg x0 and x1... or x34 and x35). We hash these x-values to produce a random 256-bit "quality string." This is combined with the difficulty and the plot size to generate the required_iterations. If the required_iterations is less than a certain number, the proof can be included in the blockchain. At this point, we look up the whole proof of space.

By only looking up one branch to determine the quality string, we can rule out most proofs. This optimization requires only around 7-9 disk seeks and reads, or about 70-90 ms on a slow hard drive.

Throughout this website, we'll make a simple assumption that a single disk seek requires 10ms. In reality, this is typically 5-10ms, so we're using a conservative estimate.

The 10ms estimate also takes into account the time required to transfer data after the seek. While storage industry specs typically assume that large files are being transferred, this does not hold true for Chia farming, where proof lookups only require a tiny amount of data to be transferred. Therefore, for this website, it's safe to assume the transfer is almost instant.

Chia also uses a further optimization to disqualify a certain proportion of plots from eligibility for each challenge. This is referred to as the plot filter. The current requirement is that the hash of the plot ID, challenge, and signage point starts with 9 zeros. This excludes 511 out of every 512 plots. The filter hurts everyone equally (except for replotting attackers), and is therefore fair. The plot filter is discussed in greater detail in the Signage and Infusion Points page.

The plot filter effectively reduces the amount of resources required for farming by 512x -- each plot only requires a few disk reads every few minutes. A farmer with 1 PiB of storage (10,000 plots) will only have an average of 20 plots that pass the filter for each challenge. Even if these plots all are stored on slow HDDs, and connected to a single Raspberry Pi, the average time required to respond to each challenge will be less than two seconds. This is well within the limits to avoid missing out on any challenges.

Each plot file has its own unique private key called a plot key. The plot ID is generated by hashing the plot public key, the farmer public key, and either the pool public key (for OG plots) or the pool contract puzzle hash (for pooled plots). The requirements for signing a proof of space depend on the type of plots being used. See the Plot Public Keys page for details on the keys used for plot construction.

In practice, the plot key is a 2/2 BLS aggregate public key between a local key stored in the plot and a key stored by the farmer software. For security and efficiency, a farmer may run on one server using this key and signature scheme. This server can then be connected to one or more harvester machines that store the actual plots. Farming requires the farmer key and the local key, but it does not require the pool key, since the pool's signature can be cached and reused for many blocks.

Verifying

After the farmer has successfully created a proof of space, the proof can be verified by performing a few hashes and making comparisons between the x-values in the proof. Recall that the proof is a list of 64 x-values, where each x-value is k bits long. For a k32 this is 256 bytes (2048 bits), and is therefore very compact. Verification is very fast, but not quite fast enough to be verified in Solidity on Ethereum (something that would enable trustless transfers between chains), since this verification requires blake3 and chacha8 operations.