Proof of Time (VDFs)

A Verifiable Delay Function, also referred to as a Proof of Time or VDF, is a proof that a sequential function was executed a certain number of times.

Verifiable: This means that after performing the computation (which takes time), the Prover can create a very small proof in a very short time, and the Verifier can verify this proof without having to redo the whole computation.

Delay: This means that the Prover actually spent a real amount of time (although we don't know exactly how much) to compute the function.

Function: This means it's deterministic: computing a VDF on an input x always yields the same result y.

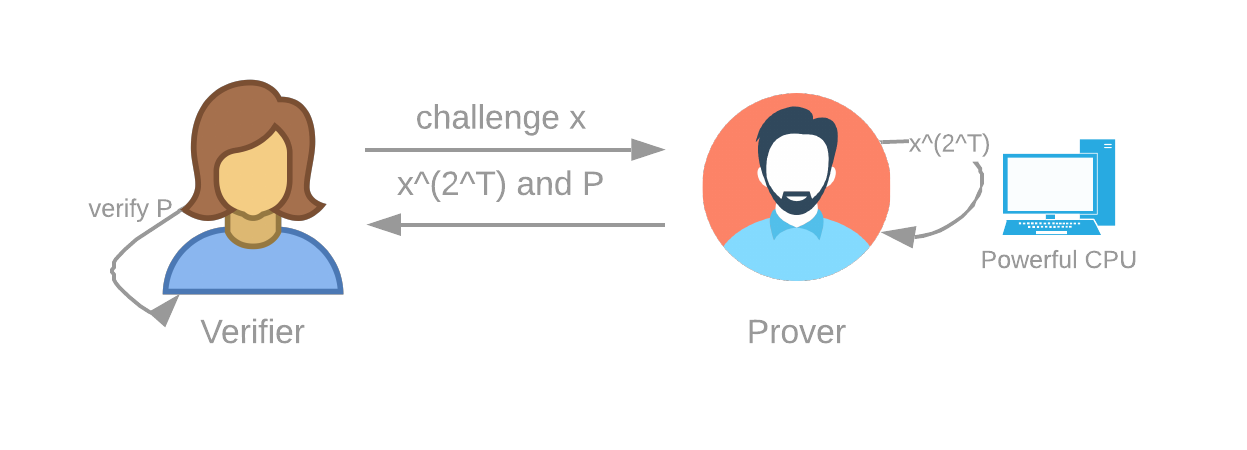

The key word here is "sequential", like hashing a number many times: hash(hash(hash(a))), etc. This means the prover cannot just add more machines to make the function execute faster. Therefore we can assume that computing a VDF requires real (wall-clock) time. The construction that we use is repeated squaring. The Prover must square a challenge x T times. This requires time ϴ(T). The Prover also must create a proof that this was performed properly.

Figure 3: The Verifier (blockchain) sends a challenge to the Prover (timelord) and the Prover computes the output and proof.

Although the following details are not very important for understanding the consensus algorithm, the choice of what VDF to use is relevant, because if an attacker succeeds in obtaining a much faster machine, some attacks become possible.

The VDF used by Chia is repeated squaring in a class group of unknown order. There are two main ways to generate a large group that has an unknown order:

- Use an RSA modulus, and use the integers mod N as a group. The order of the group is unknown if you can generate your modulus with many participating parties using an MPC ceremony.

- An easier approach is to use classgroups with a large prime discriminant, which are groups of unknown order. This does not require any complex or trusted setup, so we chose this option for Chia.

To create one of these groups, one just needs a large, random, prime number. The drawbacks are that classgroup code is less tested in real life, and optimizations are less well-known than in RSA groups. We use the same initial element for the squaring (a=2, b=1 classgroup element), and instead use the challenge to generate a new random prime number for each VDF, which is used as the discriminant. The discriminant has a size of 1024 bits, which means the proof sizes are around 1024 bits. We use the Wesolowski scheme split into n (1<=n<=64) phases so that creating the proofs is very fast. Since the n-wesolowski proofs can be large, we replace them with 1-wesolowski proofs as soon as they are available. These are smaller, but require more time to make. The proofs themselves are not committed to on-chain, so they are replaceable.

Infusion

As a recap, VDFs take in an input, called a challenge, and produce an output, together with a proof that certifies that the function was evaluated correctly.

A value, in this context, can be thought of as a block with a proof of space. The value is combined with an output of a VDF, to generate a new value, which is used as the input/challenge for the next VDF. This is known as an infusion of a value into a VDF.

Therefore, we are chaining VDFs, but committing to a new value in between. This is used so that we have a linear progression of blocks, alternating proofs of space with proofs of time.